From the classroom of Wendy Schramm (SDAWP 2016)

There are times when it pays to sit next to a master and allow their hand to rest gently over yours and guide your pen as you write.

This is the sense of comfort that I try to instill in my students as they work with mentor texts. It is also that metaphorical hand—soft, gentle, blue-veined and knowing—that has allowed my students to become increasingly comfortable with revising their own work. Here, then, is a small writing adventure that bears witness to the power of first living through another’s words and then making them your own.

In October (a lifetime ago), I decided to test out the waters of Write Out, a “two-week celebration of writing, making, and sharing inspired by the great outdoors” that is jointly sponsored by the National Parks Service and the National Writing Project. Among the writing prompts offered in support of this year’s theme, “Poetry for the Planet,” was a Choice Board that is still very much alive. We (my seventh grade students and I) chose the blue dot with the image of a buffalo and the writing invitation to “be inspired by ‘the earth Is a living thing,’ by Lucille Clifton.”

the earth is a living thing

by Lucille Clifton

is a black shambling bear

ruffling its wild back and tossing

mountains into the sea

is a black hawk circling

the burying ground circling the bones

picked clean and discarded

is a fish black blind in the belly of water

is a diamond blind in the black belly of coal

is a black and living thing

is a favorite child

of the universe

feel her rolling her hand

in its kinky hair

feel her brushing it clean

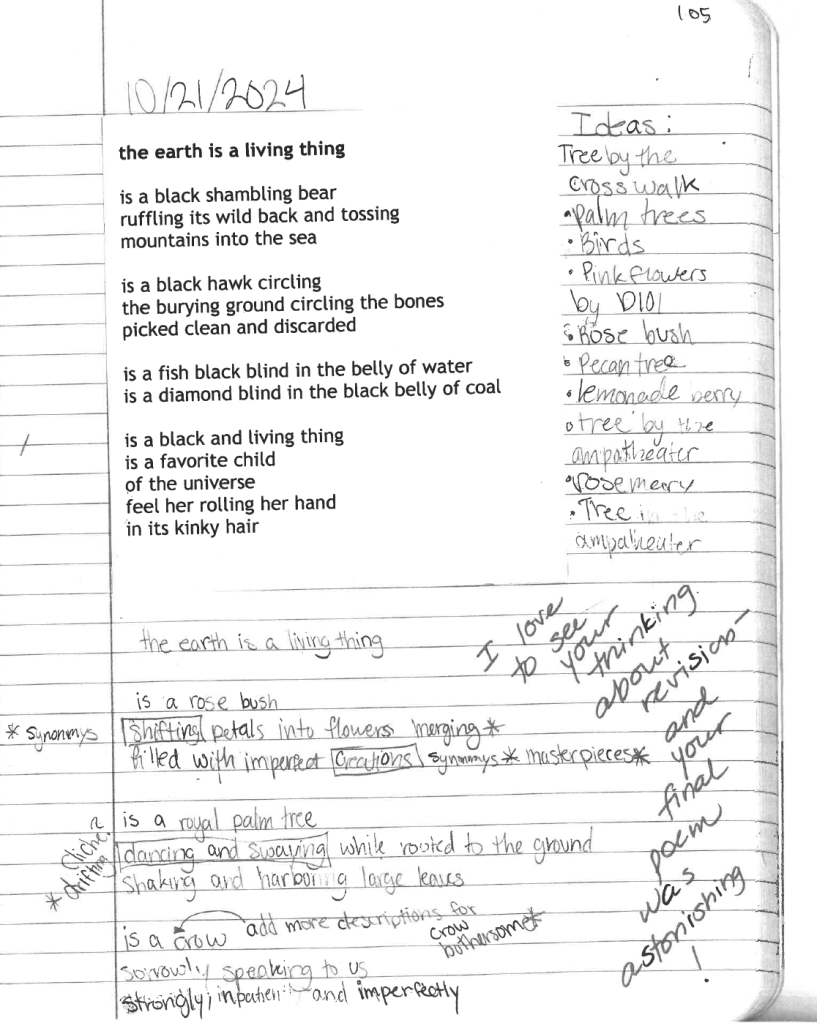

The students first pasted a copy of the poem in their writers’ notebooks, and then went on an observation-gathering walkabout on campus: strolling, watching, and then sitting quietly to jot down notes and to compose a poem using Clifton’s poem as a mentor text.

I did the same.

I rarely write when my students do, although professionals whom I admire exhort us to do just that. When my students are hard at work in their notebooks, there always seems to be an email to answer, a desk to tidy, or a planbook to update; however, this time I took the time.

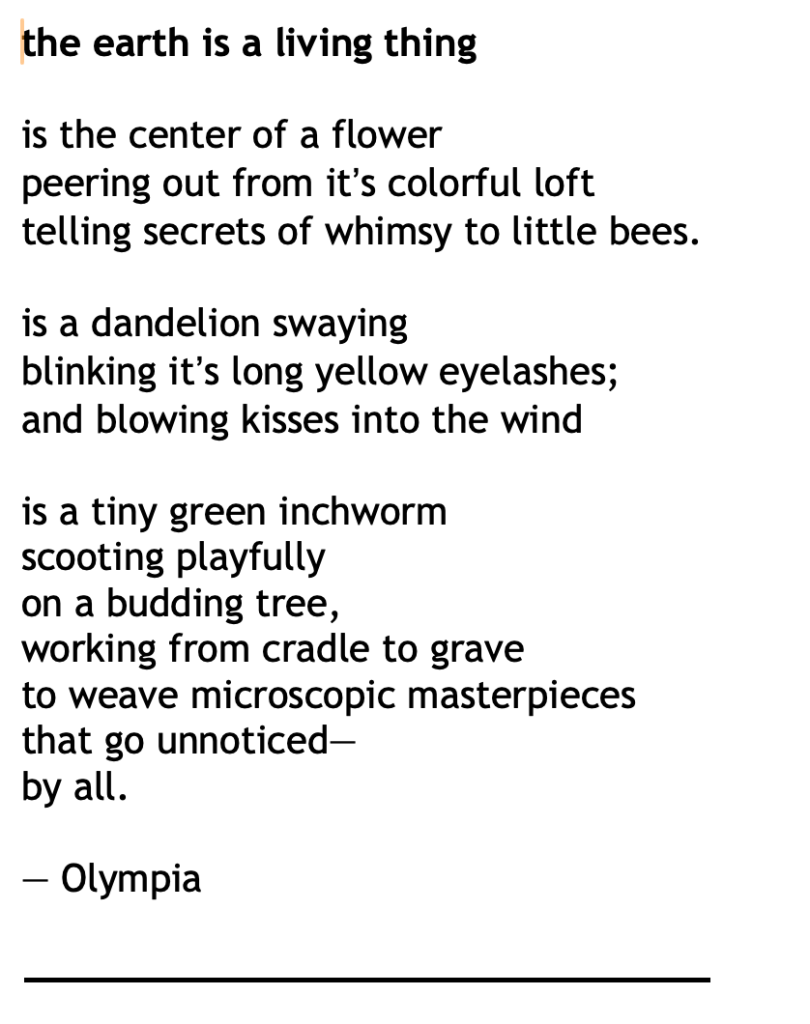

Upon returning to the classroom but before the students plucked a golden line to share aloud from their own writing, we took a look at my poem. I told them where I struggled and why. They offered thoughtful suggestions. One of their suggestions I took, another I did not, which led to a rich discussion of an author’s prerogative to accept or reject a recommendation while explaining the reasoning behind one choice or the other. Such discussions help to dispel the notion that revision is a one-way conduit from teacher edits to student acquiescence.

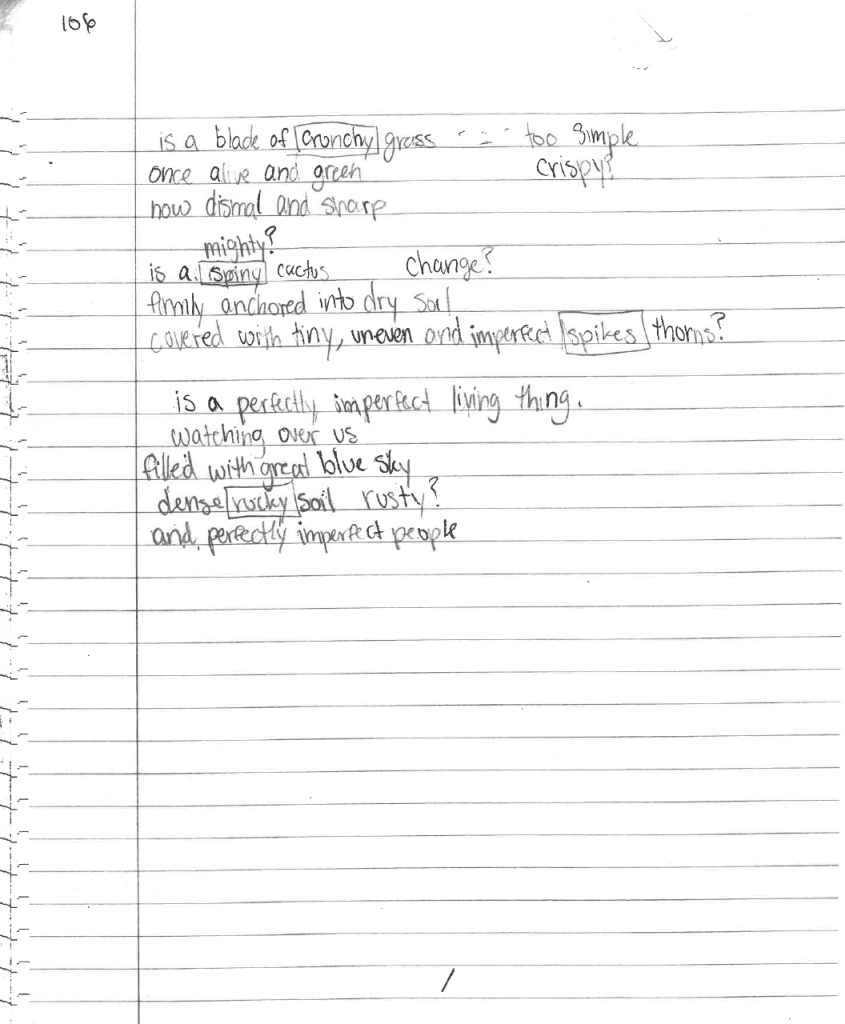

We then, each with our own poem, engaged in a three-minute “flash revision,” focusing on four key elements: replace, add, delete, rearrange, with the final recommendation that they should take a brief vacation from their work and post their final versions the following day.

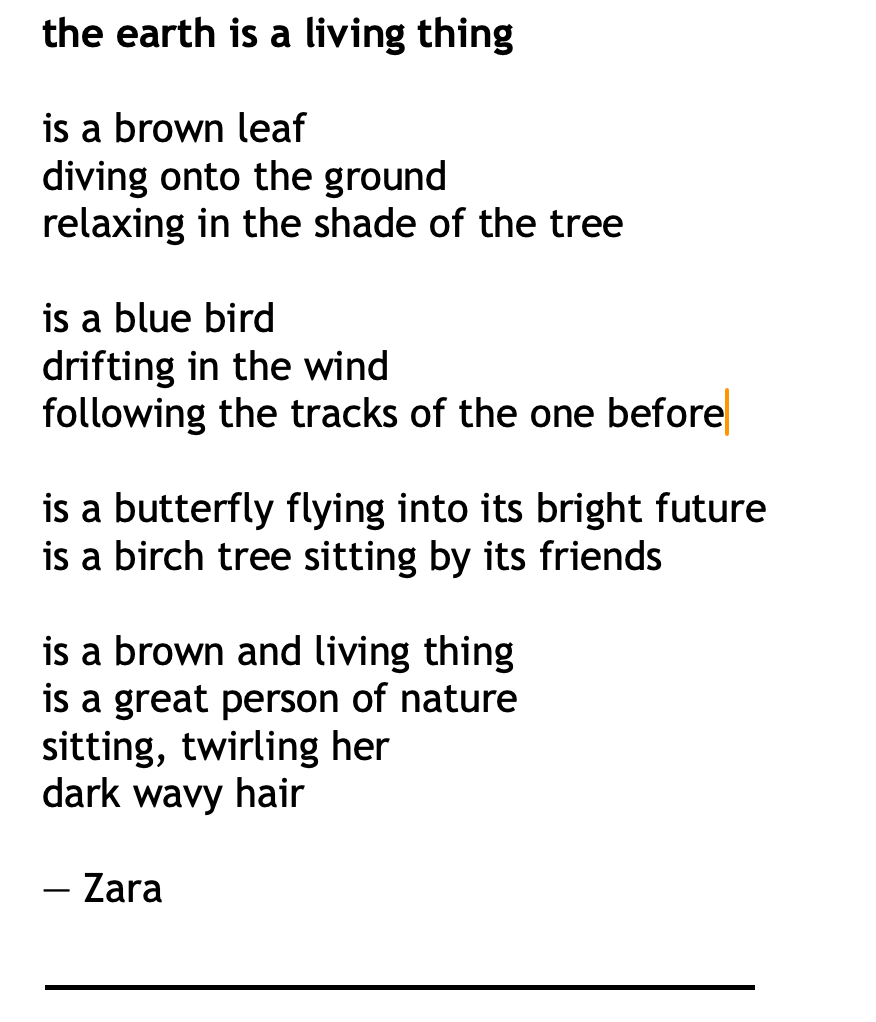

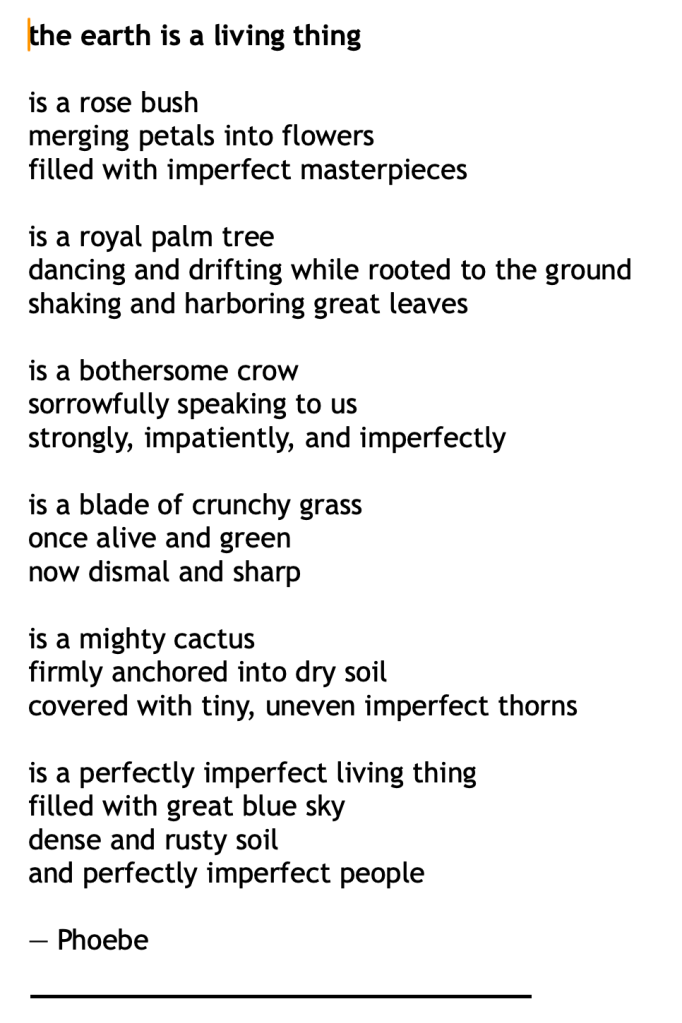

What I did not expect was how greatly many of these poems differed from what they had composed in their writers’ notebooks—more nuanced, more self-assured, more celebratory of the fact that they are, indeed, writers:

Middle schoolers are notoriously attached to their first drafts, but in extolling the virtues of revision and presenting it with a sense of joy, even seventh graders can begin to grow their writing in unexpected ways, or to borrow from one of them, they can take pleasure in a writing life “filled with imperfect masterpieces.”